What Makes a Mobile Game Great - Monetization

In Part I, I talked about the five major categories of game, which I dubbed endless, leveled, RTS, endless leveled, and personal competition. Now unless you're developing mobile games just for the thrill of people playing them, at some point you're going to want to monetize them.

Now for the overwhelming majority of the games that I discussed in the first part, they're free. The reason for this is twofold. One reason is because you can't try a game before you buy it, and if you don't like it, there's no way to return it. This greatly simplifies Apple's App Store management, but it makes it hard to invest money in a game based simply off of screenshots, a few reviews, and maybe a short clip of gameplay. The other reason is because of an adverse reaction to spending online money. Spending a dollar in cash isn't really a big deal, but spending $0.99 on an app is something that people think for a while about.

For the games that aren't free, they typically have either huge successes in previous versions, such as with Bloons TD, or Plants vs. Zombies, or they're full games in their own right, like the Infinity Blade series.

Now if your app is free, how are you going to make money? Either you go the route of ads, or the more popular route of In App Purchases. Each of the categories that I talked about have different strengths when it comes to designing these IAP's so that people want to buy them, and a lot of them.

Some games, (the one that first comes to mind is Flappy Bird) use ads. For most of them, however, they're intrusive, they lead to poor reviews of the app, and in general turn off users. One way to get around this is to have a paid version of the app without ads, and then a free version without ads. By adding this comparison, the user now believes its their choice to play with ads, and they're less likely to dislike them, and much more likely to accept them as something they wanted.

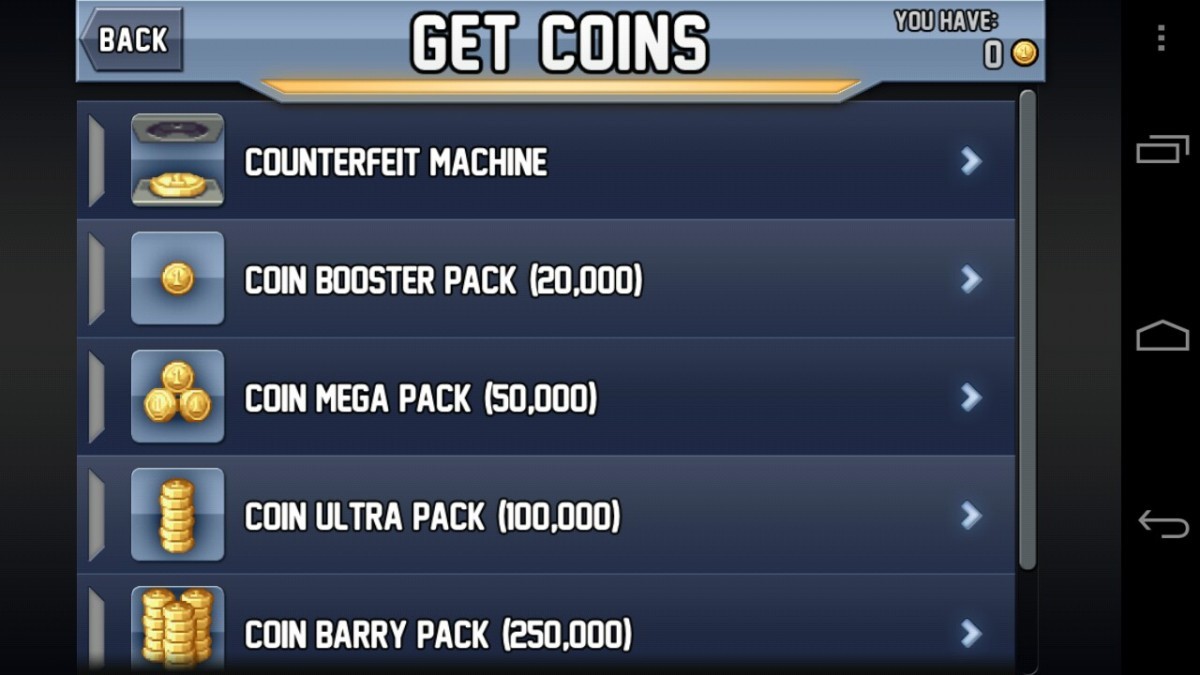

Most games use IAP. I'm gonna break down how each category of game uses them most effectively. Note that IAP should never be necessary to win the game, and really should never be used to provide the player with something they couldn't obtain through playing naturally. The best way to use them is to introduce a non IAP element into the game: some sort of "power-up" system, some leveling system, in-game currency, or a time block. Then offer IAP to purchase power-ups in bulk, to get items to boost leveling speed, or eliminate objectives that are in the way, purchase in-game currency, and reduce or remove time blocks.

Endless games tend to work best with the power-up system or leveling system, along with in-game currency. Both Jetpack Joyride and Subway Surfer have power-ups including increased or more valuable coins, "resurrections", and an in-game currency for buying cosmetic and functional permanent skill increases.

Leveled games work best with allowing you to purchase even more levels (like mini-DLC's), or boosts of in-game currency like "candy" in Cut the Rope.

RTS games work best by allowing you to reduce time. Because so much of the game is waiting, impatient players will want to speed up or reduce their wait times. By offering a bunch of speed-up items (usually gems) in the beginning of the game, and then slaking them off to next to nothing, people will want to buy them as they have already experienced the power they bring. Additionally, the longer wait times as the game goes on will both devalue current gems, and pressure users to purchase more and more often.

Endless levels work best with the power-up system of the endless games, and the time unlocks of the RTS games. Candy Crush uses both, allowing you to speed up your ability to try more and more levels, as well as getting special items that can clear the board, etc.

Personal competition games can go for a power-up system like the bombs that remove extraneous letters in Draw Something. These are one of the harder games to work IAP into without unfairly altering the playing field, and these games commonly use the free/paid ad idea to generate revenue.

So now we've gone into the ideas of games, and how to monetize. What are the take away points for making a popular, addictive, and money making hit?

- Make sure that the game can be played in down time. Chunks of the game should be playable in <5 minutes, and should always leave the player wanting more.

- Make the game easy to learn, and hard to master. This ensures that it hits a very large audience in the beginning, and makes it so that they want to keep playing.

- Reward the player heavily in the beginning, and less later. Early leveling and progress keeps people initially captured in the critical moments of whether or not they like the game. Later leveling becoming harder ensures that people keep coming along to strive for the same rush that they had earlier in the game.

- Reward the player for playing along a variable ratio schedule. This, like gambling, ensures that they constantly want to play as they never know when they could be rewarded, but do know that the reward is based on them playing a lot.

- Take something that make the game fun, and make it hard to obtain without IAP. Making it still obtainable means that people don't feel like it's pay-to-win, but because it's hard to obtain it ends up effectively being pay-to-win.

- Reward players for invitations. Rewarding invitations of other people introduces a vitality component. Connect your Facebook, so that your friends see you playing? Have some coins. Send an invite to your friend? You both get free gems. Etc.

- Take advantage of the near-miss phenomenon. People should feel like if they played again right after they lost, that they would have a better chance of winning, or that it will be very close to them winning. Take advantage of scaling difficulty to make sure the beginning is easy to get people back into the mind state of being ready to win after suffering a loss.

By taking advantage of a few basic psychological tricks, and the multitude of games that came before, you can also make a game that is creepily addicting, with the IAPs that everyone loves to hate, but keeps on buying.