Combinations and permutations and locks, oh my!

I recently bought a push button combination lock off of Amazon to hold a spare gate key (in a circular fashion so Amazon delivery drivers could deliver me even more packages, because worker's rights concerns 1 Despite this and countless boycott attempts, Amazon boasts 168M+ US users with Prime and consistently polls at the top of net favorability scores across Big Tech. Turns out it's beneficial to deliver a product that people actually like and find useful! pale in comparison to same-day shipping of ethernet switches 2 My apartment was wired for ethernet, but the runs were left dangling unterminated in the garage. After hyping myself up with a couple of YouTube videos and discovering the miracle of cheap wire testers (that you can learn any skill on YouTube is also a miracle, but wire testers are black magic) I gave fixing it myself a go, wiring it all into a punch panel and connecting it through an ethernet switch—only to not have it work. After 15 minutes of self-flagellation that found nothing wrong I took apart the wall plates that the builders had run, only to discover they had miswired the terminator in every room. Sometimes it really isn't your fault. ). It's supposed to be a rekeyable lock, where you can choose the code. When it comes to rekeyable locks I have three basic expectations: that you can set a code, that entering that code again would open it, and that entering the wrong code would not. What this lock presupposes is "what if only the first two were true"?

Why I got confused

If you search "combination lock" on Google you'll get what I imagine as the platonic ideal for a high school locker: 3 or 4 numbers set by fiddly wheels that are always stuck, or a spinning dial that requires me to Jimmy Neutron-brain blast 3 Can you believe that this was Oscar nominated? Alongside Monster's Inc and Shrek (which won). Baffling, and to me almost as unbelievable as the movie preceding the TV show, given how singularly weird the town and side characters are. to remember how to open it.

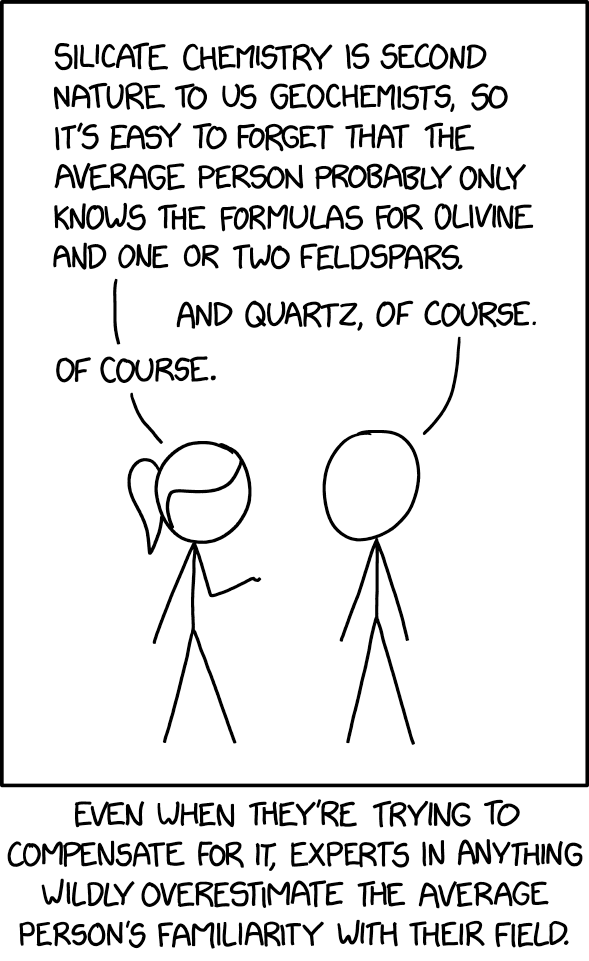

However while these are colloquially called "combination locks" this conflicts with the mathematical definition of "combination", which is used to describe unordered arrangements, e.g. where \( \set{1, 2, 3} \) is the same as \( \set{3, 2, 1} \). More accurately pedantically these would be better described as "permutation locks" because order matters: if 32-17-25 opened the lock in the upper left, then 17-25-32 wouldn't. Unfortunately because assuming that the average person understands combinatorics terminology is a losing game

4

these are all named combination locks, which means that when I buy a push button combination lock I think it'll also be a permutation. Wrong!

these are all named combination locks, which means that when I buy a push button combination lock I think it'll also be a permutation. Wrong!

How a push button combination lock works

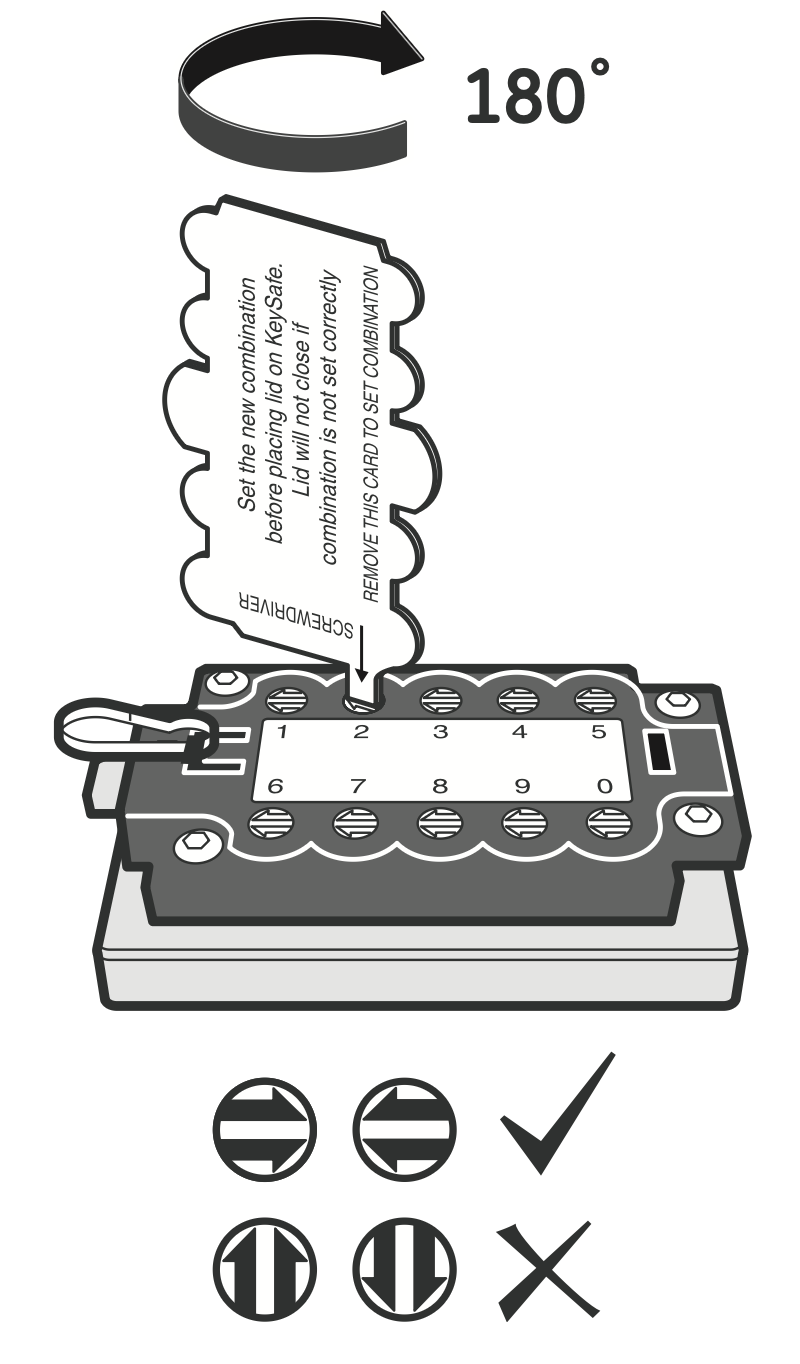

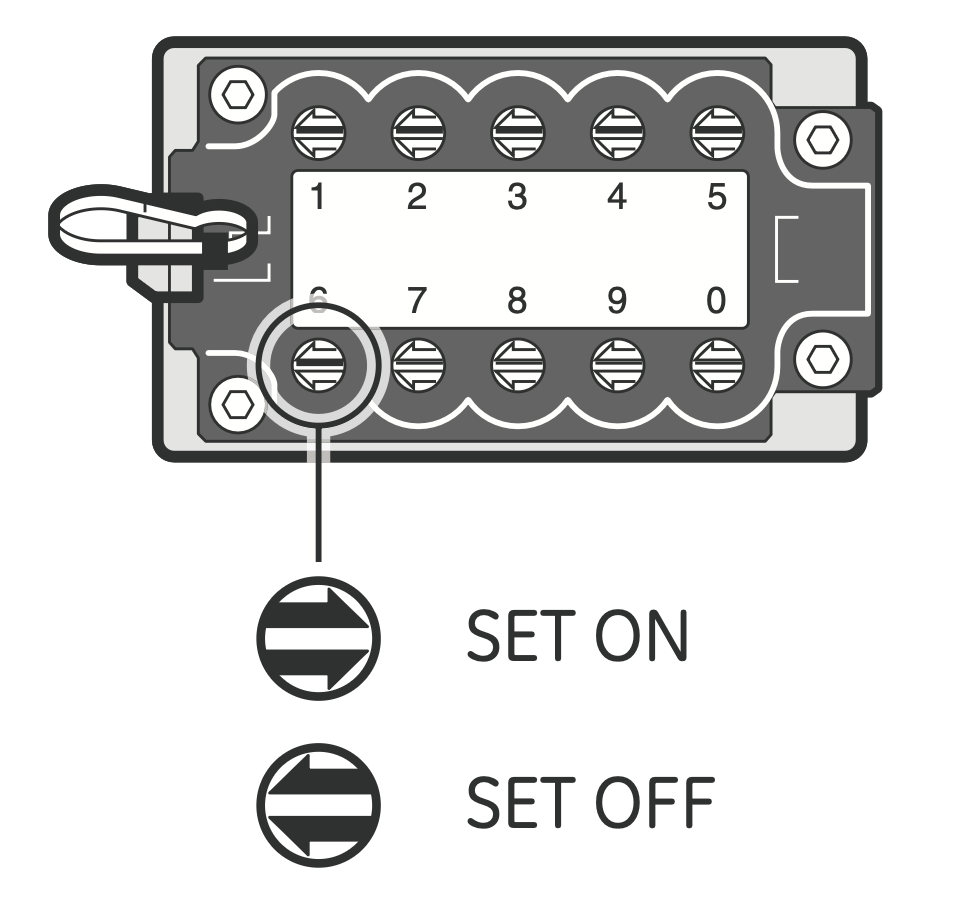

Instead it's a true combination lock, where it doesn't matter what order you enter the code in. You can see this from the manual where setting the code has no concept of order: each number is either on or off. 5 These are color coded to make later parts of this writeup more followable.

Use the tool to rotate each number...

Use the tool to rotate each number...

...either setting it to on to be part of the code, or off to not.

...either setting it to on to be part of the code, or off to not.

If this feels like it has a lot fewer potential codes than something like a Master Lock, you're right. A Master Lock "combination" lock has three numbers from 1-36, which is \(36^3 = 46{,}656\) ordered triples 6 Kind of. I don't think Master Lock allows duplicates, machine tolerances for the gates drop this number under 6k, and regardless you can reverse engineer the code for one in just a few minutes. as opposed to \(36*3 = 108\) if it was unordered. Unlike a Master Lock though, the push button box allows you to set as many digits as you want, so rather than just having \(10*3\) options there are a whopping...actually, how many options are there?

There's two ways to go about this. We have a set of 10 numbers, and each potential code for the box is comprised of some subset of these numbers. How many subsets are there? For each of the 10 numbers, I can either include the number or leave it out, which is 10 choices each with two options, or \(2^{10} = 1{,}024\).

Another way would be to consider the number of ways you could have a code with no digits (1 possible code), only one digit (10 possible codes), two digits (10 choices for the first, 9 for the second, so 90, except order doesn't matter so halve it to get 45), and so on. This is written as \(\binom{10}{0} + \binom{10}{1} + \binom{10}{2} + \ldots\) or \(\sum_{n=0}^{10} \binom{10}{n}\). These are calculating the same thing so tada, we've rederived the sum of binomial coefficients from first principles! 7 Maybe my math major wasn't useless after all! (Editor's note: it was).

$$ \sum_{n=0}^{k} \binom{k}{n} = 2^k $$

Manual's odd hint

Interestingly despite there being 1,024 potential combinations the manual recommends something interesting for choosing a code during setup:

Use five to seven numbers in your combination.

This recommendation drops you from 1,024 combinations to a measly 582, and while on first glance a 7-digit combination might feel more secure, there's actually fewer codes than a 4-digit combination, 210 vs. 120.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 45 | 120 | 210 | 252 | 210 | 120 | 45 | 10 | 1 |

Why would they recommend this? It's possible that if people are trying to break into one of these locks they'll start with 3- or 4-digit codes, so a 7-digit code buys more time. It's also possible that the manual's author just didn't think that hard about it. But there may actually be a good reason for it. To explain it though, we're going to have to find a better answer to the question posed by the previous section: how does a push button combination lock really work.

How a push button combination lock really works

The only real reference I could find to how these work mechanically was from a video intro explaining how to break into one of these 8 This is foreshadowing for the answer. I am a master of subtlety. from the LockPickingLawyer: 9 Known for opening Master Locks in seconds among...other things (a video in which he coincidentally uses the exact lockpick that almost got me expelled from college). His videos are interesting but if you ever want to go down a lockpicking YouTube rabbit hole here's the key and lock that've lived rent free in my head for over a decade.

"Behind the keypad is a sliding plate that's attached to the open button. Each of the number buttons is over a notched rod that goes through that plate. By pushing the correct buttons, we align the notches in those rods with the plate and that allows it to slide fully. That in turn opens the lock."

I didn't fully understand it in a way that I thought I could explain to someone else,

10

"Feynman was a truly great teacher. He prided himself on being able to devise ways to explain even the most profound ideas to beginning students. Once, I said to him, "Dick, explain to me, so that I can understand it, why spin one-half particles obey Fermi-Dirac statistics." Sizing up his audience perfectly, Feynman said, "I'll prepare a freshman lecture on it." But he came back a few days later to say, "I couldn't do it. I couldn't reduce it to the freshman level. That means we don't really understand it."" — Feynman's Lost Lecture, p.52

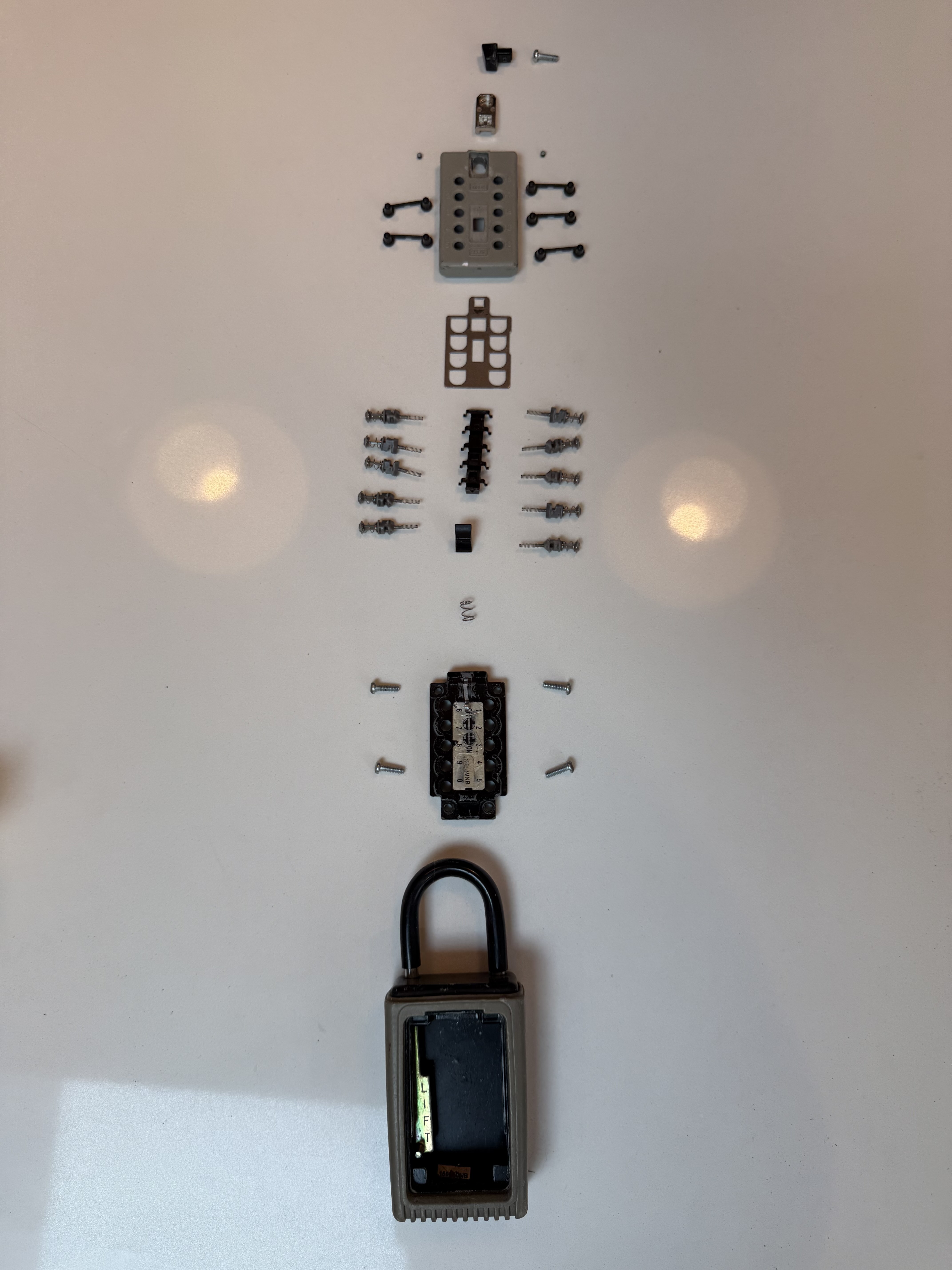

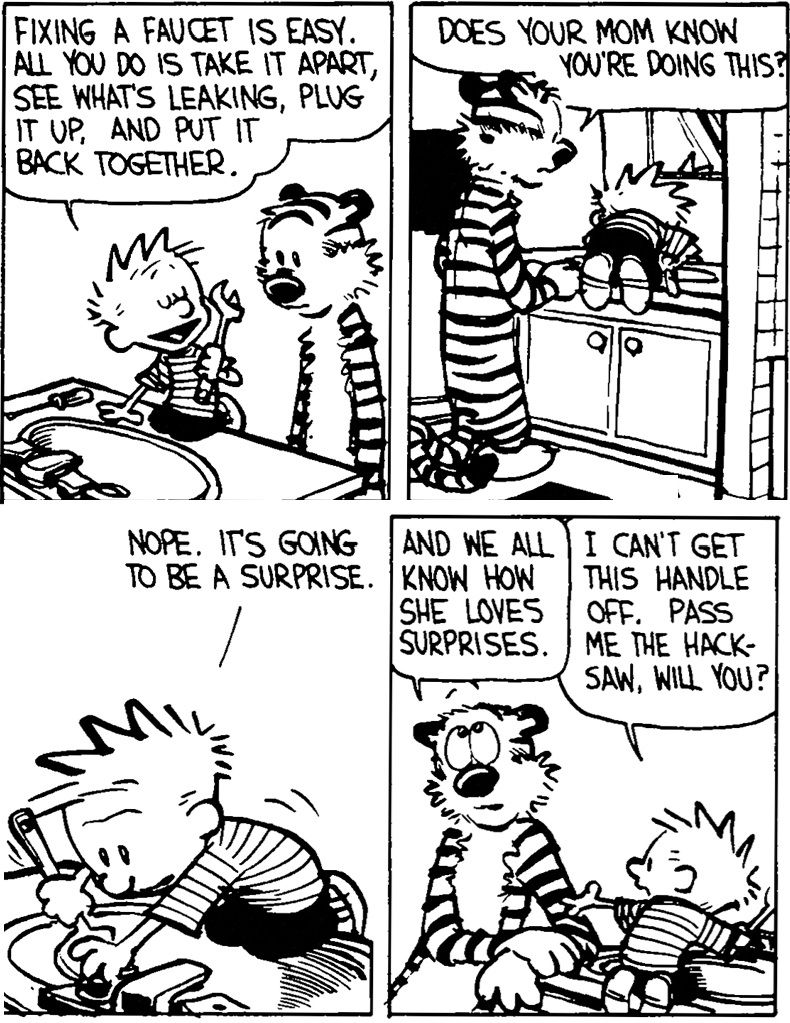

even after watching a related lock's disassembly, and two 3D renders of similar push button mechanisms. What's the best way to learn how something works? Take it apart and put it back together.

11

Note that putting it back together is a crucial part of this.

Lock body

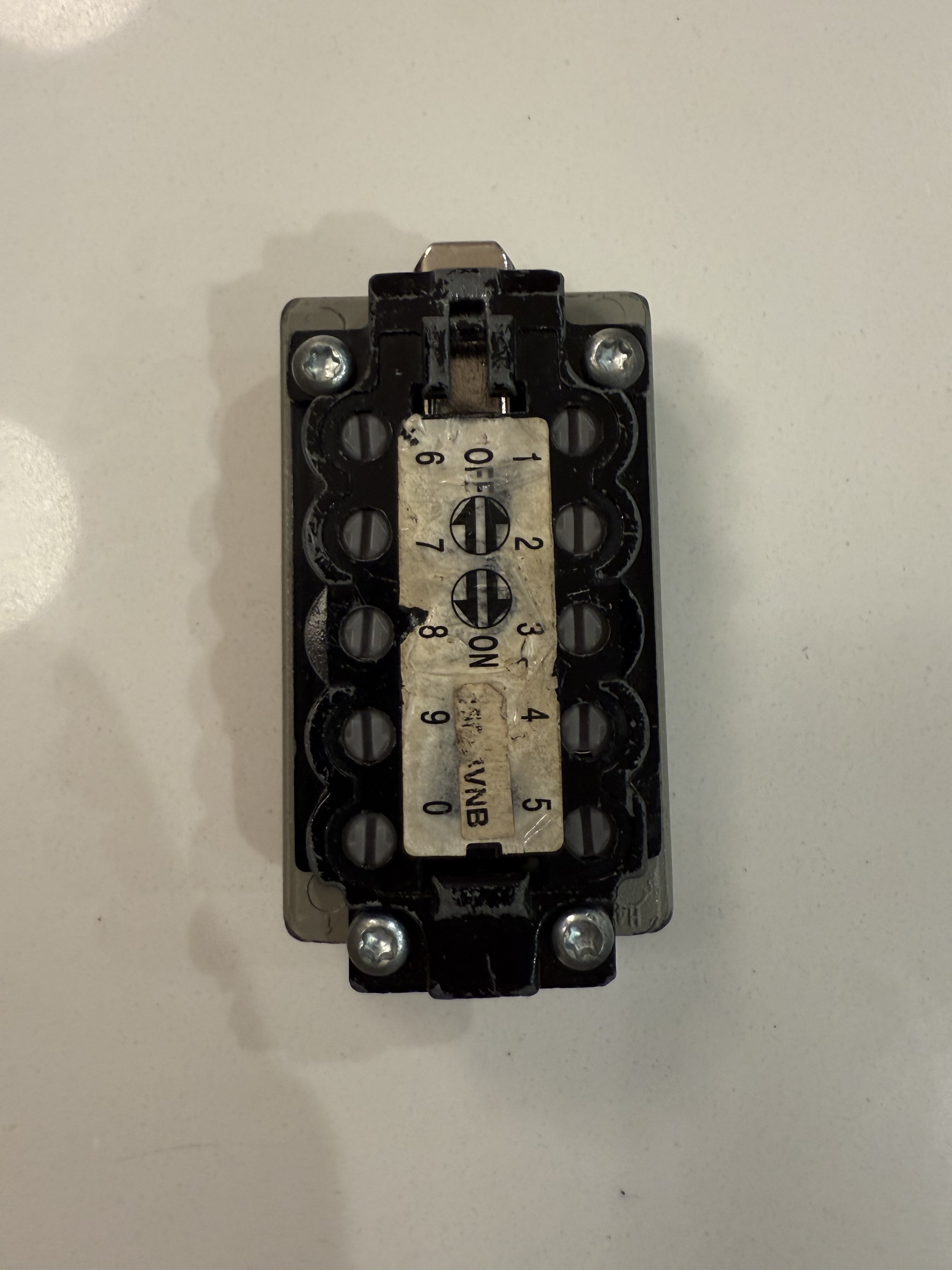

If you open the lock box the metal piece at the top is allowed to slide down and out of the way, releasing the lock face from the rest of the chassis. The back of the lock face is pictured below, and if you zoom in you can just make out its combination.

Unscrewing the four Torx screws

12

Created by Bernard Reiland back in the late 60s to prevent cam-out, something that he won an award for from the International Fastener Institute a mere month before he died in 2008. Who knew that the International Fastener Institute existed—the world really is fractal—but the Torx screws are certainly better for not stripping the head (unless you're me, who unscrewed it using a flathead across a diagonal).

allows you to remove the black back plate, and reveal that it's all under spring tension. The video

13

This video came from my iPhone, which helpfully encodes everything with HDR that darkens the entire website on Mac to try and show even brighter whites. Luckily I found this resource to reformat the video without blowing out the converted .mp4, which for future reference is the very succinct ffmpeg -i IMG_4859.MOV -c:v h264_videotoolbox -maxrate 2600K -bufsize 2600K -vf "zscale=t=linear:npl=100,format=gbrpf32le,zscale=p=bt709,tonemap=tonemap=hable:desat=0,zscale=t=bt709:m=bt709:r=tv,scale='trunc(iw/2):trunc(ih/2)',format=yuv420p" -c:a aac IMG_4859.mp4 (if you're curious, the link has an explanation).

also shows the first glimpse of the plastic pins that make up the main lock mechanism.

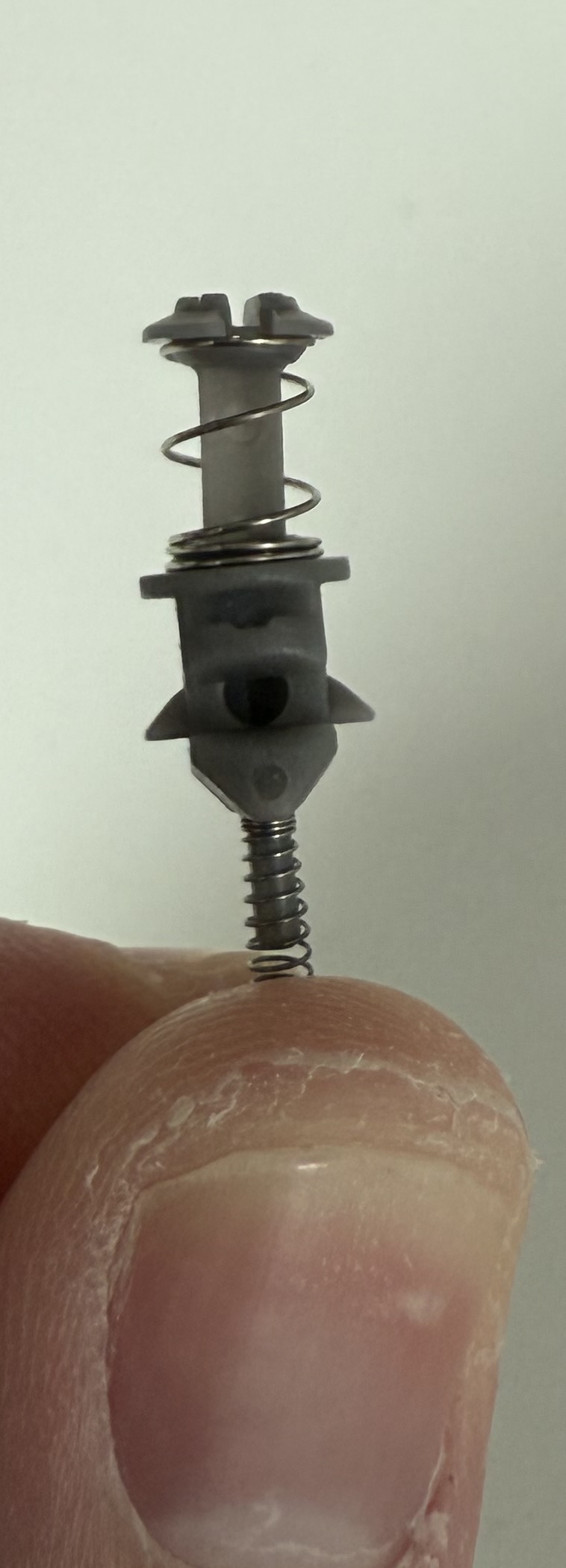

Pins

The pins are composed of two separate pieces held together by spring tension (when not disassembled). Each bottom piece is attached to a push button and held in place via a spring, which I'm holding in the photos. The top piece is held in place by the black plate, and has the arrow you can turn to choose if a digit is part of the code. The top piece only serves to rotate the bottom piece and keep tension: the bottom piece is what actually interacts with the sliding plate.

From the side view in the first image you can see two sets of indents, each with a deeper groove and a shallower groove. When successfully unlocking the sliding plate will either go into the top deeper groove when a digit is off and therefore not in the code, or the bottom deeper groove when the digit is on and in the code.

Sliding plate

The sliding plate is made of machined aluminum, with holes for eight of the pins. There aren't ten because the pins only interact with the thin bars (either going into the deeper groove for a correct pin or the shallow groove for an incorrect pin), so the bottom of the plate covers the last two pins. In addition to the eight identical cutouts there's three more holes: one at the top that connects to the front unlock slider with a screw; a square one in the middle where the metal piece at the top that locks the box is affixed; and a rectangular one in the middle that seems to be unused. 15 Maybe just to reduce weight and material? I may have just missed something, there's probably a good reason — Chesterton's fence. There's also a small cutout on the right side that helps orient the piece and restrict how far it can slide. 16 This is also quite useful if the locks are manual assembled: always make doing something the right way easier than the wrong way.

Under tension the pins sit by default with the top cutout in line with the plate. This is why 'off' points towards the top of the lock: you're orienting the pin so that the plate can slide cleanly into the unpressed position. If the pin is oriented on then it needs to be raised so the plate can slide into the bottom cutout. But how do the pins raise and stay raised once pressed?

Pin latch mechanism

With the plate removed you can see a nestled black plastic piece, composed of a central rod with ten thin "arms" that act as a compliant mechanism. 17 Mark Rober has a true talent for turning these concepts into massively popular videos. All I'm doing is writing overly long blog posts when I get nerdsniped by a purchase. When a button is pressed, its corresponding pin is pushed upwards. The pin has a latch tab with an angled shape that pushes the corresponding plastic arm out of the way until it's above it, when the deformed plastic arm snaps back into its normal position, latching under the tab and keeping it elevated.

With the sliding plate removed, you can see the pin latch mechanism

With the sliding plate removed, you can see the pin latch mechanism

Plastic pin latch piece with "arms" for each pin

Plastic pin latch piece with "arms" for each pin

Two latch tabs on the pin so that it works regardless of orientation

Two latch tabs on the pin so that it works regardless of orientation

The pin will stay elevated until the latch piece is pushed down, sliding the arms out of the way of the latch tabs so all pins reset. This happens when the clear button on the front of the lock is pushed as you can see in the video. It also happens if the lock is opened, as the metal plate sliding open fully depresses the latch.

Latch moving independent of the metal plate  The metal moves the latch too via the black plunger at the bottom

The metal moves the latch too via the black plunger at the bottom

The rest of the owl

Nothing else matters to the functioning of the lock, but I laid it all out just to show the pieces. One interesting point is that instead of ten buttons for each pin there's only five pieces, each levering to cover two buttons (which is why you can press two buttons in different rows at the same time but not two buttons in the same row).

But even with all of these pictures and all of these words it's a little hard to grasp how the core functionality works. So let's take a page out of Bartosz Ciechanowski's book 18 All of his writeups are fantastic, but his renders especially are so good at iteratively building understanding of complex topics. The watch one I linked and his article on Light and Shadows might be my favorites, but they're all good: if you haven't read them you should. and build some interactive renders!

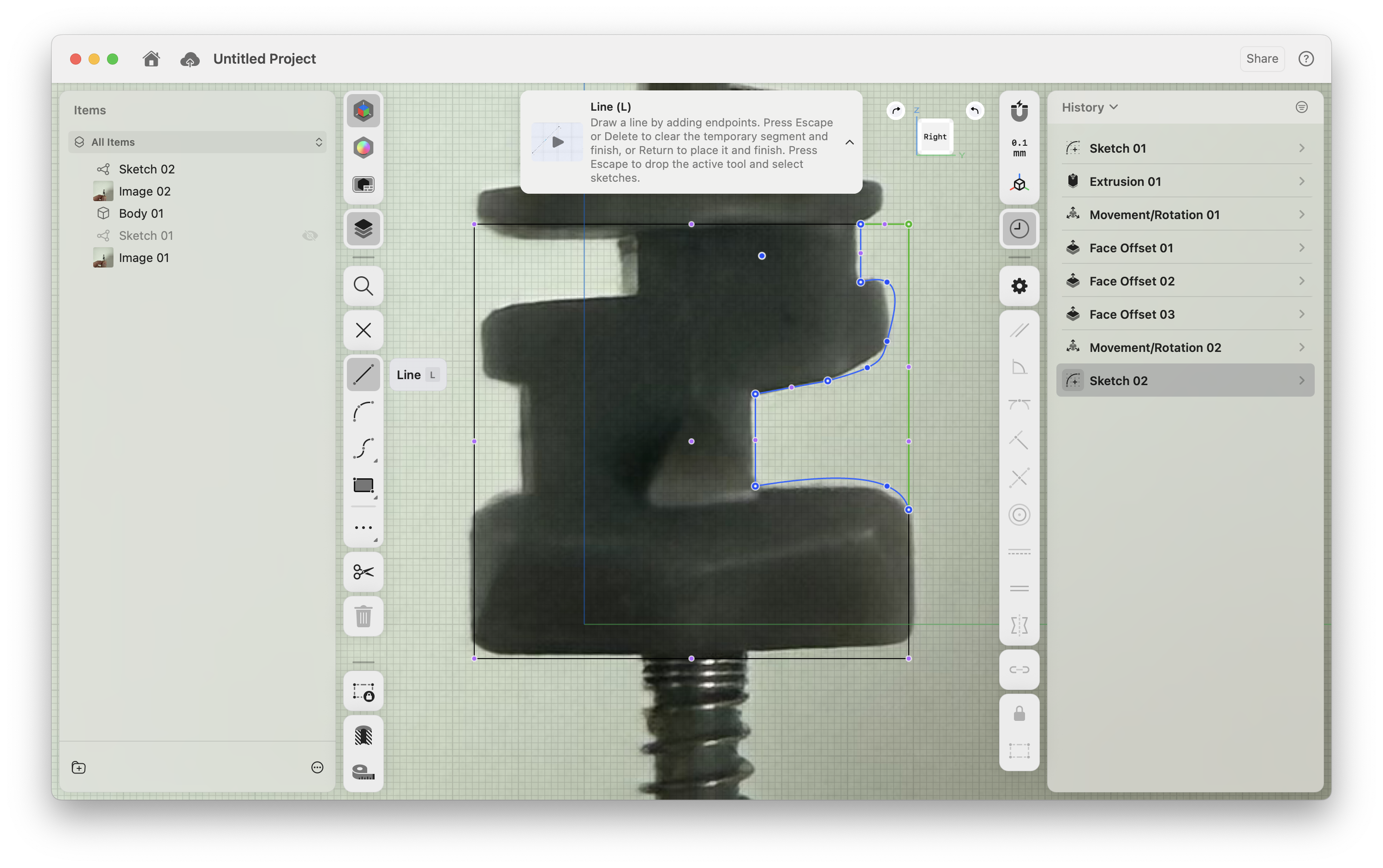

Rendering

I started wanting to just render a single pin to make it rotatable and easier to visualize. I'd never used any CAD software so I wanted to skip modeling entirely, figuring that if AI world models like Genie 3 were out then surely there were some cheap programs that could make me a 3D model from images. Unfortunately Cube by CSM ($5) didn't make something workable, and neither did Meshy (free, but didn't allow exports

19

But it loads the .glb file to render the preview, so...

) or MakerLab's Image to 3D from MakerWorld (free). That being said this existing at all is a miracle, and I imagine at the rate of improvement this is a solved problem by next year.

940 KB)

15.2 MB)

14.2 MB)

The Cube one isn't that bad (Meshy is horrendous), but none of them get the latch tabs right. Unfortunately there was only one option left:

20

I love backing myself into corners, it's such a great way to learn.

hire someone on Fiverr teach myself CAD. After bouncing off Auto Fusion I saw that Bartosz himself had used Shapr3D so figured I'd give it a go. I'll second his opinion: Shapr3D was much more intuitive. The pricing scheme makes it hard to recommend, but with a 2 week free trial I was good to go for this writeup.

21

It's free for students and teachers but I'm neither, so it's $38/month if you want reasonable export options. I'd love to pay per export, but there's unfortunately no real desire to support hobbyist pricing. Still, great great software with a nice built-in tutorial. If I were to do it again, I might try OnShape, which has a free tier.

I pulled the image in, and with a little bad tracing, extrusions, and some artistic liberties with no attention paid to true measurements

22

This slapdash approach makes for a much less polished product than Bartosz's mathematically precise outputs, but if anything it's maybe more realistic for cheap lock production tolerances.

three hours later I had some basic .glb files exported (and at only 283 KB I managed to be more accurate than Meshy at \(\frac{1}{50}\)th the size).

23

Again, "accurate" is doing some heavy lifting. A lot of stuff doesn't line up right because it's eyeballed. Just pretend :D.

Without further ado, here's the interactive version. I made a number of simplifications: I turned the pins from two pieces into one, I color coded them red for off and not part of the code and green for on, I removed all springs, and I flattened the pin latch (just pretend the pins are briefly deforming the arms instead of phasing through them). Keep in mind that the buttons in the faux-lock actually push the bottom of these pins, so if you , the top left pin is actually 6 and the top right is 1: to make it match the lock UI you have to (click to go back to normal).

I recommend trying and failing to open the lock! I also recommend looking specifically at how the tabs interact with the pin latch when pressed, and how the aluminum plate intersects each pin during a successful and failed unlock attempt. You can freely rotate, zoom and pan (Shift+drag on desktop) the rendering. You can also click pins to change whether they're part of the code or not.

Now that we have a rough sense of how the lock internally works we can answer the original question: why would we potentially want more numbers involved?

Picking the lock

We're going to jump back to the video I referenced about breaking into one. The approach described is to hold the unlock button down, causing the metal plate to bind with all of the pins. For the pins that are off, the plate will be in the deeper groove, and they'll have less wiggle room. By pressing on the buttons a seasoned hand can detect the ones that are binding and locked in place, meaning that they're not part of the code.

If, however, most of the pins are part of the code they'll in aggregate prevent the metal plate from getting that far into even the deeper off grooves. You might think you can just do the process in reverse by pushing up all the pins and testing what binds in the second set of grooves. Unfortunately the pins being held up by the latch mechanism heavily dampen the amount of feedback you get from the buttons, making this considerably harder (and something that was pointed out in the comments on the YouTube video):

At the end of the day though, there's still only a thousand options. The real key to avoid people picking your lock? Pick a different lock.

-

Despite this and countless boycott attempts, Amazon boasts 168M+ US users with Prime and consistently polls at the top of net favorability scores across Big Tech. Turns out it's beneficial to deliver a product that people actually like and find useful! ↩︎

-

My apartment was wired for ethernet, but the runs were left dangling unterminated in the garage. After hyping myself up with a couple of YouTube videos and discovering the miracle of cheap wire testers (that you can learn any skill on YouTube is also a miracle, but wire testers are black magic) I gave fixing it myself a go, wiring it all into a punch panel and connecting it through an ethernet switch—only to not have it work. After 15 minutes of self-flagellation that found nothing wrong I took apart the wall plates that the builders had run, only to discover they had miswired the terminator in every room. Sometimes it really isn't your fault. ↩︎

-

Can you believe that this was Oscar nominated? Alongside Monster's Inc and Shrek (which won). Baffling, and to me almost as unbelievable as the movie preceding the TV show, given how singularly weird the town and side characters are. ↩︎

-

These are color coded to make later parts of this writeup more followable. ↩︎

-

Kind of. I don't think Master Lock allows duplicates, machine tolerances for the gates drop this number under 6k, and regardless you can reverse engineer the code for one in just a few minutes. ↩︎

-

Maybe my math major wasn't useless after all! (Editor's note: it was). ↩︎

-

This is foreshadowing for the answer. I am a master of subtlety. ↩︎

-

Known for opening Master Locks in seconds among...other things (a video in which he coincidentally uses the exact lockpick that almost got me expelled from college). His videos are interesting but if you ever want to go down a lockpicking YouTube rabbit hole here's the key and lock that've lived rent free in my head for over a decade. ↩︎

-

"Feynman was a truly great teacher. He prided himself on being able to devise ways to explain even the most profound ideas to beginning students. Once, I said to him, "Dick, explain to me, so that I can understand it, why spin one-half particles obey Fermi-Dirac statistics." Sizing up his audience perfectly, Feynman said, "I'll prepare a freshman lecture on it." But he came back a few days later to say, "I couldn't do it. I couldn't reduce it to the freshman level. That means we don't really understand it."" — Feynman's Lost Lecture, p.52 ↩︎

-

Note that putting it back together is a crucial part of this.

↩︎

↩︎ -

Created by Bernard Reiland back in the late 60s to prevent cam-out, something that he won an award for from the International Fastener Institute a mere month before he died in 2008. Who knew that the International Fastener Institute existed—the world really is fractal—but the Torx screws are certainly better for not stripping the head (unless you're me, who unscrewed it using a flathead across a diagonal). ↩︎

-

This video came from my iPhone, which helpfully encodes everything with HDR that darkens the entire website on Mac to try and show even brighter whites. Luckily I found this resource to reformat the video without blowing out the converted

.mp4, which for future reference is the very succinctffmpeg -i IMG_4859.MOV -c:v h264_videotoolbox -maxrate 2600K -bufsize 2600K -vf "zscale=t=linear:npl=100,format=gbrpf32le,zscale=p=bt709,tonemap=tonemap=hable:desat=0,zscale=t=bt709:m=bt709:r=tv,scale='trunc(iw/2):trunc(ih/2)',format=yuv420p" -c:a aac IMG_4859.mp4(if you're curious, the link has an explanation). ↩︎ -

I'm not exactly sure what these are called, but I'm using 'latch tab'. Remember these, we'll come back to them. ↩︎

-

Maybe just to reduce weight and material? I may have just missed something, there's probably a good reason — Chesterton's fence. ↩︎

-

This is also quite useful if the locks are manual assembled: always make doing something the right way easier than the wrong way. ↩︎

-

Mark Rober has a true talent for turning these concepts into massively popular videos. All I'm doing is writing overly long blog posts when I get nerdsniped by a purchase. ↩︎

-

All of his writeups are fantastic, but his renders especially are so good at iteratively building understanding of complex topics. The watch one I linked and his article on Light and Shadows might be my favorites, but they're all good: if you haven't read them you should. ↩︎

-

But it loads the

.glbfile to render the preview, so... ↩︎ -

I love backing myself into corners, it's such a great way to learn. ↩︎

-

It's free for students and teachers but I'm neither, so it's $38/month if you want reasonable export options. I'd love to pay per export, but there's unfortunately no real desire to support hobbyist pricing. Still, great great software with a nice built-in tutorial. If I were to do it again, I might try OnShape, which has a free tier. ↩︎

-

This slapdash approach makes for a much less polished product than Bartosz's mathematically precise outputs, but if anything it's maybe more realistic for cheap lock production tolerances. ↩︎

-

Again, "accurate" is doing some heavy lifting. A lot of stuff doesn't line up right because it's eyeballed. Just pretend :D. ↩︎